Table of contents

2. Introduction

2.1 Problem context

Pesticides are a topic of considerable policy interest across environmental, agricultural and human health legislation. There is widespread interest in pesticides from regulators, farmers and the public owing to potential risks they present for both the environment and public health. Under the Water Framework Directive, pesticides are second only to nitrates in causing most failures of good chemical status in groundwater (European Commission, 2019).

For a topic of such interest, at a European level we know surprisingly little about the actual levels of pesticides in surface and ground waters. The sorts of reasons impacting on our knowledge include:

- Countries monitor a number of different pesticides, but the reported data on pesticide concentrations in waters are very different in quality and quantity and therefore difficult to harmonise to obtain an established European overview.

- Pesticide use depends on the crop type, season, weather and equipment availability. Some estimates of pesticides in the environment are based on sales data, but this gives very little indication of actual use or concentrations and toxicity of pesticides in water.

- Monitoring and assessment of pesticides in surface waters is mostly done routinely, but pesticide peaks in surface waters can only be identified by event-based monitoring, such as following heavy rainfall.

- Pesticide pollution from point sources could also be attributable to substances used in biocide products (e.g. household products, facade paint, gardening), which enters the water cycle mainly through discharges from urban waste water treatment plants (UWWTP), storm overflow or urban run-off. There is limited understanding of the significance of such contributions relative to those from agriculture.

Alongside these specific issues, there is also concern about the role pesticides may play in mixture toxicity. Existing environmental quality standards apply to single substances but in the environment, organisms are exposed to chemical mixtures. We know little about the combined effects of such mixtures but there is a risk that chemicals could combine to reach harmful levels (EFSA, 2019; EEA, 2018a; Busch, 2016; Kortenkamp, et al., 2009b). Given the uncertainty but the knowledge that pesticides are harmful to at least part of an ecosystem, application of the precautionary approach would seem appropriate.

2.2 Aim and scope of the report

The aim of this technical report is to provide an overview of information available on pesticides in surface and groundwater, based on reported information. This report includes descriptions and assessments of available data from different data and information sources with a focus on the European level.

The focus of this report is on active pesticide ingredients in agricultural activities (see section 2.3 for definition). It needs to be mentioned, that once a substance reached the environment, it is not usually possible to ascertain the original source or use of it. Organisms experiencing the resultant mixture do not discriminate by source, though such information is helpful in identification of appropriate prevention measures. Other chemicals which may be present in the water are out of scope of this technical report.

2.3 Definition and classification of pesticides

According to FAO (2002), pesticides are defined as follows:

“Any substance or mixture of substances intended for preventing, destroying, or controlling any pest, including vectors of human or animal disease, unwanted species of plants or animals, causing harm during or otherwise interfering with the production, processing, storage, transport, or marketing of food, agricultural commodities, wood and wood products or animal feedstuffs, or substances that may be administered to animals for the control of insects, arachnids, or other pests in or on their bodies. The term includes substances intended for use as a plant growth regulator, defoliant, desiccant, or agent for thinning fruit or preventing the premature fall of fruit. Also used as substances applied to crops either before or after harvest to protect the commodity from deterioration during storage and transport” (FAO 2002).

EU legislation divides pesticides into plant protection products and biocides. The term ‘pesticide’ is often used interchangeably with ‘plant protection product (PPP)’, however, pesticide is a broader term that also covers non plant/crop uses, for example biocides [1]. These PPPs are products including ‘pesticide substances’ that protect crops or desirable or useful plants. They are primarily used in the agricultural sector but also in forestry, horticulture, amenity areas and in gardens. The products contain at least one active substance and have one of the following functions:

- protect plants or plant products against pests/diseases, before or after harvest;

- influence the life processes of plants (such as influencing their growth, excluding nutrients);

- preserve plant products;

- destroy or prevent growth of undesired plants or parts of plants.

EU countries authorize plant protection products on their territory and ensure compliance with EU rules (see section 2.5).

[1] Source: https://www.efsa.europa.eu/en/topics/topic/pesticides

Overall, pesticides are grouped in different ways depending on the defining interest group, usage or others. Main classifications are usually based on a biological, chemical or technical basis. Whereas the biological goal seems to be very relevant e.g. the pests they control or the target organisms they kill, inhibit or destroy in one way or another, other important definitions derive from their chemical structure (e.g. organophosphate insecticides or neonicotinoids, organochlorine etc.) or their method of application. The definitions between these groups are rather fluid but most often the classification might clearly define all of the four main pesticide classes: “an insecticidal acetyl-choline esterase inhibiting fumigant pesticide of the organophosphate substance class” (Lewis, et al., 2016).

Based on the given definitions, grouping of pesticides within this report were based on their usage and their mode of action (MoA). This grouping is in a way comparable to the EFSA (European Food Safety Authority) based “Cumulative Assessment Group or CAG” [1].

According to their usage, the report focusses on the three groups (i) herbicides, (ii) insecticides and (iii) fungicides. The herbicides should control unwanted plants, insecticides are used to prevent unwanted insect infestation, and fungicides to kill parasitic fungi or their spores.

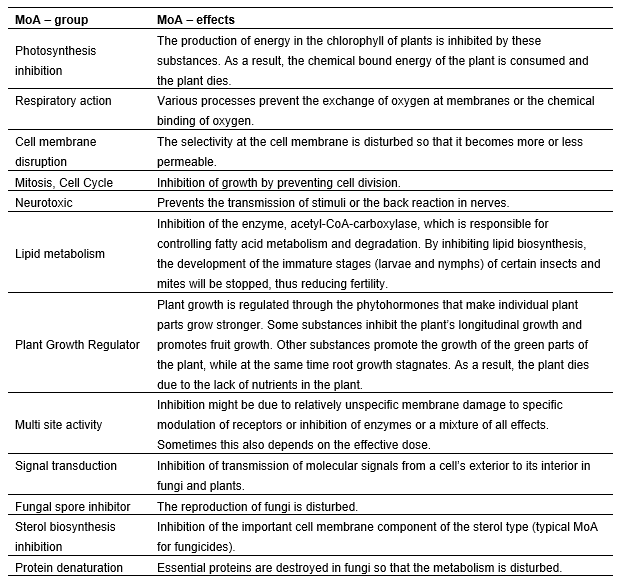

The classification according to the MoA of pesticides is oriented towards their effects in the non-human organisms. Table 2.1 lists the different MoA, which were assigned to the pesticides available under Waterbase – Water Quality in the time period 2007 – 2017 (see Annex 5).

[1] Source: http://www.efsa.europa.eu/en/consultations/call/180508-0

Table 2.1 Groups of pesticides according to mode of action (MoA) and their effects to organisms

Note: Based on the used methods, data availability and data selection, only photosynthesis inhibition and neurotoxic MoA were assessed (see section 4.1.1.1)

2.4 Sources, uses and sales of pesticides

Pesticides are substances contained as active ingredients in plant protection products and biocides. They must selectively act against specific pest organisms, but it is impossible to achieve absolute selectivity (i.e. where effects are limited to only the target species). Furthermore, some pesticides being toxic to humans and/ or harming the environment by contaminating soil, surface and ground water. Pesticide contamination of both surface and groundwaters can affect aquatic fauna and flora, as well as human health when pesticide polluted water is used for public consumption. Aquatic organisms are directly exposed to pesticides resulting from agricultural production or indirectly through trophic chains (Maksymiv, 2015).

The pesticide pollution from agricultural activities of surface waters or groundwater may have different sources: a) Diffuse losses, e.g. spray drift due to pesticide application, b) point sources from waste water treatment plants (run-off from farmyards connected to sewer systems), c) surface run-off from farmyards during cleaning of application techniques, and d) leaching to field drains or to shallow groundwater (Sandin, 2017; Aktar, et al., 2009). In addition to agricultural activities, other relevant sources for pesticides include forestry, municipial use (e.g. on roadside), grasslands (e.g. golf courses) and uses in gardens. Once pesticides reach streams, they can be widely dispersed into other streams, rivers, lakes, reservoirs, and oceans (USGS, 1997).

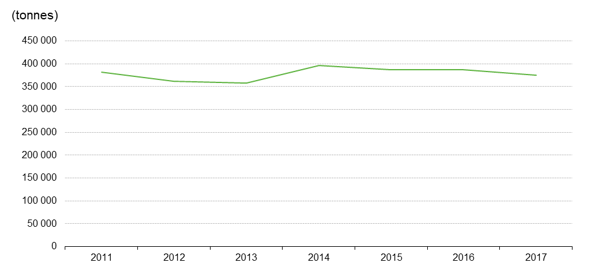

Population growth, increase in food consumption, and export of agricultural products (crops as well as meat) result in enhanced agriculture production, which mostly relies on extensive use of pesticides (FAO & IWMI, 2017). In Europe, the volume of pesticide sales has remained about constant since 2011 (Figure 2.1). The groups with the highest sales are fungicides, bactericides and herbicides (some 80% of the total pesticide sale). France, Italy, Spain and Germany sold together over 65 % of the total volumes reported in the EU (Agri-environmental indicator - consumption of pesticides - Statistics Explained 2019). However, the share of tonnes of pesticide sales does not allow any statement about the risk to human health and the environment.

Figure 2.1 Sales of pesticides, EU-28, 2011-2017

Note : This figure does not take into account confidential values. They represent < 3% of the total of sales over the entire time series.

Source : Eurostat (online data code : aei_fm_salpest09). https://ec.europa.eu/eurostat/statistics-explained/images/1/18/Sales_of_pesticides%2C_EU-28%2C_2011-2017_%28tonnes%29.png

Based on sales data, EEA developed the ‘Total sales of pesticides’ indicator under the 7th Environment Action Programme within priority objective 3 to safeguard the Union’s citizens from environment-related pressures and risks to health and well-being (EEA, 2018a). It indicates no trends of pesticide sales (grouped by their usage) from 2011 to 2016. It is also stated, that: “This indicator does not allow, at present, for a full evaluation of progress towards the 2020 objective as pesticide sales are not synonymous with the risk of harmful effects on humans and the environment” (EEA, 2018a).

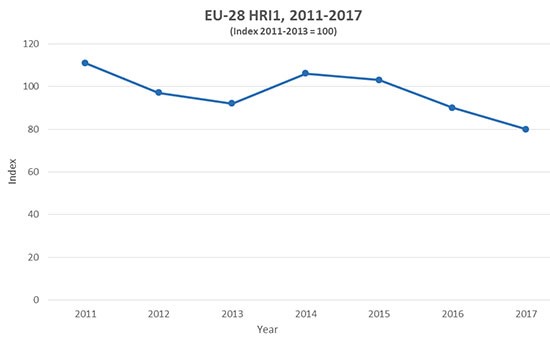

Beside the sales of pesticide information, EU developed the Harmonised Risk Indicator (HRI) to support the goals of the Sustainable use of pesticides Directive (EU, 2009). The HRI, published in 2019, considers the quantities of active substances placed on the market in plant protection products, and shows a decreasing trend from 2011 to 2017 of some 20% (Figure 2.2). This caused surprise among some [1].

Figure 2.2 Harmonised Risk Indicator 1

Note: A baseline of the average of three years 2011-2013 is used as the starting point against which subsequent values are compared.

Source: https://ec.europa.eu/food/plant/pesticides/sustainable_use_pesticides/harmonised-risk-indicators/trends-hri-eu_en

[1] Source: https://www.endseurope.com/article/1666559/commission-pesticides-data-draws-scepticism

There is a need for the development of a management tool such as an indicator which would combine the information on concentrations in water with the ecotoxicological knowledge of the specific pesticide product or its active components. This way regulators and politicians would be able to search, detect, identify the most important (i.e. most toxic and in highest concentrations) pesticide in their region of interest and prioritise management actions.

2.5 Legislation and broader regulation on pesticides

The European Union tackles water pollution since the 1970s, e.g. Council Directive on pollution caused by certain dangerous substances discharged into the aquatic environment (EU, 1976), the Urban Waste Water Treatment Directive – UWWTD (EC, 1991), the Drinking Water Directive – DWD (EU 1998) or the Nitrates Directive (EU, 1991). Since 2000, the Water Framework Directive became the central instrument of water management and protection of EU waters (EC 2000). For substances (including pesticides), two daughter directives added quality standards to be achieved.

For source control, Directives and Regulations were set on substance level for a standardized registration including risk assessment or, for example, the usage of specific substances in agriculture as pesticides.

The following list of Directives and Regulations distinguishes between water policy and source control legislations including pesticide substances:

Water policy

- The Water Framework Directive (WFD) (EC 2000) sets a scheme for water management at river basin level. With regular six yearly planning and programmes of measures a good status of surface and groundwater is to be achieved.

- The WFD daughter Directives on Environmental quality standards in water policy - EQSD (EU, 2008) and on groundwater (EU, 2006a) set quality objectives and targets for pesticides in surface and groundwater.

- The Drinking water directive (EU 1998) sets quality objectives for pesticides at the tap.

Register and source control legislation according to pesticide substances

- Regulation on the European Pollutant Release and Transfer Register (E-PRTR) (EU, 2006b), which is the Europe-wide register that provides accessible key environmental data from industrial facilities in European countries including substances used as pesticides or biocides.

- The REACH Regulation (EC, 2006) aims to improve the protection of human health and the environment through identification and risk assessment of chemical substances, and to register the information in a central database.

- The Directive on the sustainable use of pesticides (EU, 2009) aims at reducing the risks and impacts of pesticide use on human health and the environment, and promoting the use of integrated pest management and alternatives such as non-chemical approaches.

- The Plants Protection Products Regulation (EC, 2009b) set out rules for the authorisation of plant protection products and their marketing, use and control. Based on this Regulation, the Seventh Environment Action Programme (EU, 2013) set the objective that, by 2020, the use of plant protection products should not have any harmful effects on human health or unacceptable influence on the environment, and that such products should be used sustainably.

- The Biocide Regulation (EU, 2012) focusses on the marketing and use of biocide products.

The UN Stockholm Convention recommends the ban of specific substances, inter allia pesticides, to protect human health and the environment from persistent organic pollutants (UNEP 2018) [1].

[1] List of persistent organic pollutants: http://chm.pops.int/TheConvention/ThePOPs/AllPOPs/tabid/2509/Default.aspx