Table of contents

- Draft key messages

- Executive summary

- 1 Introduction - 1.1 Scope of theme: Why care about floodplains?

- 1 Introduction - 1.2 The catchment-river-floodplain ecosystem and policies

- 2 Floodplains under pressure - 2.1 Floodplain characteristics and extent

- 2 Floodplains under pressure - 2.2 Current floodplain status in Europe

- 2 Floodplains under pressure 2.3 - Climate change and altered flood risk

- 2 Floodplains under pressure - 2.4 Hydromorphological pressures and alterations

- 2 Floodplains under pressure - 2.5 Pollution pressures

- 3 Improving ecosystem services and measures - 3.1 Ecosystem services

- 3 Improving ecosystem services and measures - 3.2 Measures

- 3 Improving ecosystem services and measures - 3.3 Examples of river and floodplain restoration

- 4 Managing from an ecosystem perspective

- 5 Conclusions and Outlook

- References

- Annex 1 European and Global Policy Context

- Annex 2 Definitions

- Annex 3 Ecosystem service overview

- Annex 4 Measures that improve services

4 Managing from an ecosystem perspective

Optimal management of floodplains requires strategies that aim at reducing economic losses and threats to human lives due to floods, while at the same time protecting the natural resources and functioning of floodplains.

The practical implementation of the Water Framework, Floods, Habitats and Birds Directives takes place through implementation of management plans. Whereas River Basin and Flood Risk Management Plans operate on the scale of river basin districts (180 river basin districts have been designated across Europe), the Habitat and Birds Directives operate with management plans for each Natura2000 site (more than 27 000 sites, covering 18% of Europe’s territory (EEA, 2019c)).

Closing the implementation gap

In EU Member States, there are increased incentives in considering nature based solutions. Most countries report on using nature based solutions as measures in their Flood Risk Management plans (EC, 2019), and EU Member States are improving river hydromorphology as part of the River Basin Management Plans. Measures aimed at improving longitudinal continuity, river restoration, improvements of riparian areas, removal of hard embankments, improvements of flow regime or nature based solutions are reported. Moreover such solutions have been found to be a cost-efficient means of reducing flood risk while at the same time supporting other ecosystem oriented objectives (EEA, 2017b).

There are, however, also gaps in implementation. The analysis of the first Flood Risk Management Plans showed that almost all countries consider some aspect of climate change, but only 10 EU Member States had serious reflections of climate change impacts (EC, 2019). Many Member States could not factor in the impact of climate change on the magnitude, frequency and location of floods. Generally, historical data were used. They carry the risk of not reflecting future weather conditions or potential changes in the frequency and severity of floods (ECA, 2018). Improving these assessments will be a key effort in the next round of Flood Risk Management Plans. The outlook of altered flood risk due to climate change, further emphasises the importance of establishing Flood Risk Management Plans that consider possible changes to flooding in coming years together with the need for increased water retention. Investments in restoration projects made through programmes like LIFE + is likely to act as an EU level driver for more river and floodplain restoration building on methods that enable natural water retention.

The need for more holistic planning recognised by the Strategic Environmental Assessment Directive (EC/42/2001), which requires that plans such as the flood risk, river basin, or protected sites management plans are assessed in regards to their ability to promote over all sustainable development. It is used as a tool to assess cross boarder coherence of river basin management plans in international river basin districts and to secure that planned development indeed is sustainable from the point of view of cross-policy environmental objectives. Often considerations under this Directive lead to altering plans towards more sustainable solutions (EC, 2015).

The more forward looking question of what is actually needed to meet targets across directives, within a catchment and on a decadal timescale, however, remains unanswered. Possibly, this gap could be filled by an ecosystem based management approach where the impact of multiple land use activities is reconciled against environmental objectives. Although the need for river and floodplain restoration is widely acknowledged through the Water Framework, Floods, Habitats and Birds Directives, it is usually not assessed from a holistic river basin management perspective, nor are restoration needs considered at the scale of a catchment or river basin. Restoration measures are in competition with many other uses of the river-floodplain system, and a more holistic analysis could support balancing management priorities. Large river restoration project are costly and time demanding undertakings. Hence it is natural and probably also desirable that they are carried out one project at the time. However, a perspective on restoration needs within a river basin, from a holistic and cross-policy perspective could be very helpful for informing the management and planning process.

Improved coherence

Many decisions related to water management also have profound impact on habitats and species that depend on water. While river basin and flood risk management plans attempt to coordinate measures, this is less the case with Natura 2000 management plans. An assessment of the Natura 2000 network concluded that the network had not been implemented to its full potential, in part due to incomplete management plans and follow-up (ECA, 2017). Coordination across the Water Framework, Floods, Habitats and Birds Directives may also be hampered by the large difference in scale between the planning areas. However, as shown in this analysis, many of the services provided by the floodplain also benefit biodiversity, and the measures that achieve improved ecological and conservation status are often the same.

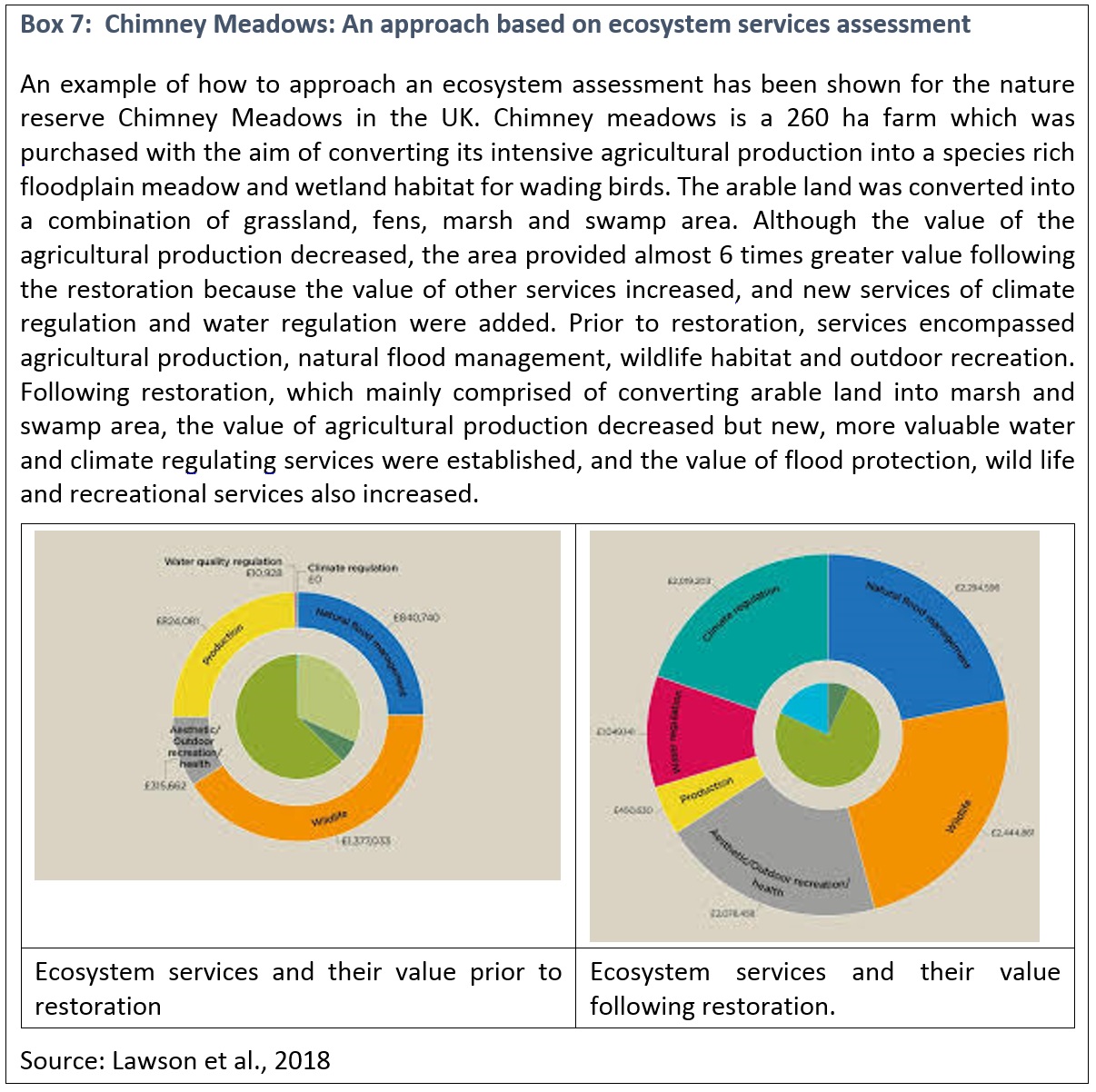

Managing from the perspective of ecosystem services enable a system where the relationship between services and trade-offs between competing service provision can be evaluated. This is not straightforward to accomplish, but compelling examples such as the restoration of Chimney Meadows, UK that demonstrate an almost 6 fold increase in value of a restored area through consideration of multi-functional aspects of the area (Box 7), suggest that there is a lot to be gained using such approaches. Once a holistic assessment of watershed or river basin priorities are available, it becomes more straightforward to inform the planning process on management trade-offs needed to establish a more sustainable use scenario.

The example for Chimney Meadows suggests, improved floodplain management can be achieved through optimisation of the ecosystem services delivered by implementation of specific restoration measures. This is, however, a complex undertaking, and achieving positive results requires a combination of political prioritisation, planning of relevant measures, corporation among multiple governing institutions, as well as an active stakeholder process, often spanning across years. Although such processes are often challenging and difficult, there are many examples of very positive outcomes.

As shown in the example of Chimney Meadows, the delivery of provisioning services tend to take place at the expense of regulating & maintaining and cultural services, and in this example, reducing the intensity of provisioning services, gave rise to increased value of other services. Realising this potential often requires restoration and changed land use practices.

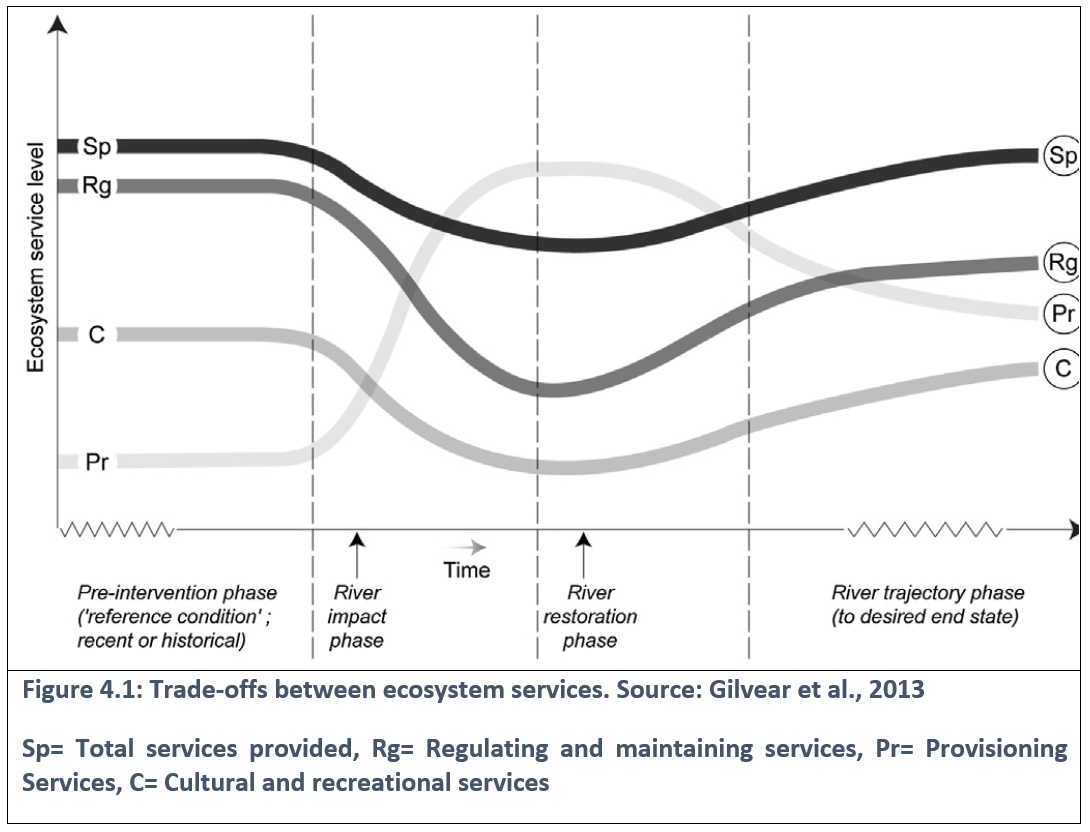

Recently, it has, however, become increasingly apparent that there are considerable benefits to be realised from this more holistic approach. Through restoration, it may be possible to initiate a development trajectory over time where the overall value of ecosystem services is increased (Figure 4.1). Historically, rivers have undergone an impact phase, with high priority given to provisioning services. In a river restoration phase, the increased value of regulating and cultural services is prioritised, although possibly at the expense of provisioning services. However, the result of the restoration could be a higher overall value of the services delivered. The overall aim of holistic planning should be to establish the needs of this development trajectory.

Improved cooperation

It is important that all stakeholders are involved in the prioritisation process. The quality of their cooperation whether institutions, authorities or the public, influences the outcome of implementation (Sander, 2018). Water management authorities typically work at river basin and catchment scales, while land use planners typically work at the scale of administrative areas, such as municipalities. As a result, their planning units often do not match up, creating barriers in terms of integration (EC, 2014).

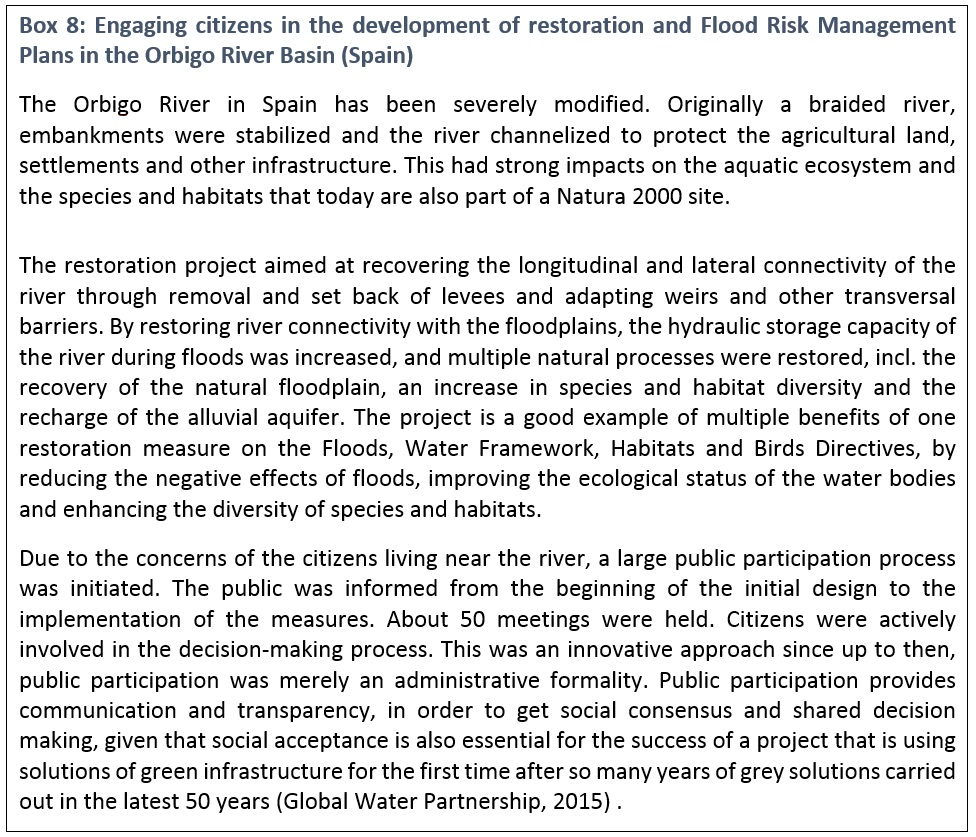

Floodplain restoration projects will face large opposition if they do not make sense to the local community or to landowners affected by the restoration. Hence, in the planning phase there is a need to be transparent in communicating the project aims and to be open to changes. Overall, public support has been found to be essential for the success and acceptance of floodplain restoration measures. It has also been found that once completed, a large majority of the local population greatly value the restored area. An analysis of public acceptance towards river restoration in Germany found that even in full awareness of the costs of restoration projects (approximately 400,000 Euros per river km), 70% of the interviewees regard further restoration projects as useful and only 6% as not useful (Deffner and Haase, 2018). An example of citizen engagement is provided in Box 8,