Table of contents

1 Introduction

This report was initiated following the EEA 2018 European waters: status and pressures 2018 to highlight the role of agriculture in achieving improved status of surface and groundwater in future river basin management plans (EEA, 2018c). The EEA five yearly State of the environment assessment, further highlights the need for an increasingly systemic approach to overcome environmental challenges and to achieve sustainability.

In this report it is analysed how agricultural production affects water quality, quantity and aquatic ecosystems, as well as the relevant policy interventions. With the aim of addressing how the water-agriculture-food system could be better managed, the work is organised around two guiding assessment questions:

- How does the current system of managing agricultural pressures on water work?

- What is needed to improve environmental outcomes?

As agriculture covers 40% of Europe’s terrestrial area, it is not surprising that agricultural production has a major impact on Europe’s aquatic environment. The main pressures from agriculture on water are diffuse nutrient and chemical pollution, water abstraction and hydromorphological pressures. These pressures impact water quality, quantity, ecology, and biodiversity in Europe’s rivers, lakes, transitional and coastal water bodies as well as the marine environment (EEA, 2018c). Agriculture also impacts biodiversity, soils and contributes around 10 % of greenhouse gas emissions(EEA, 2019g, chapters 3 and 13)) . These impacts are not discussed in this report, although they are certainly of equal importance.

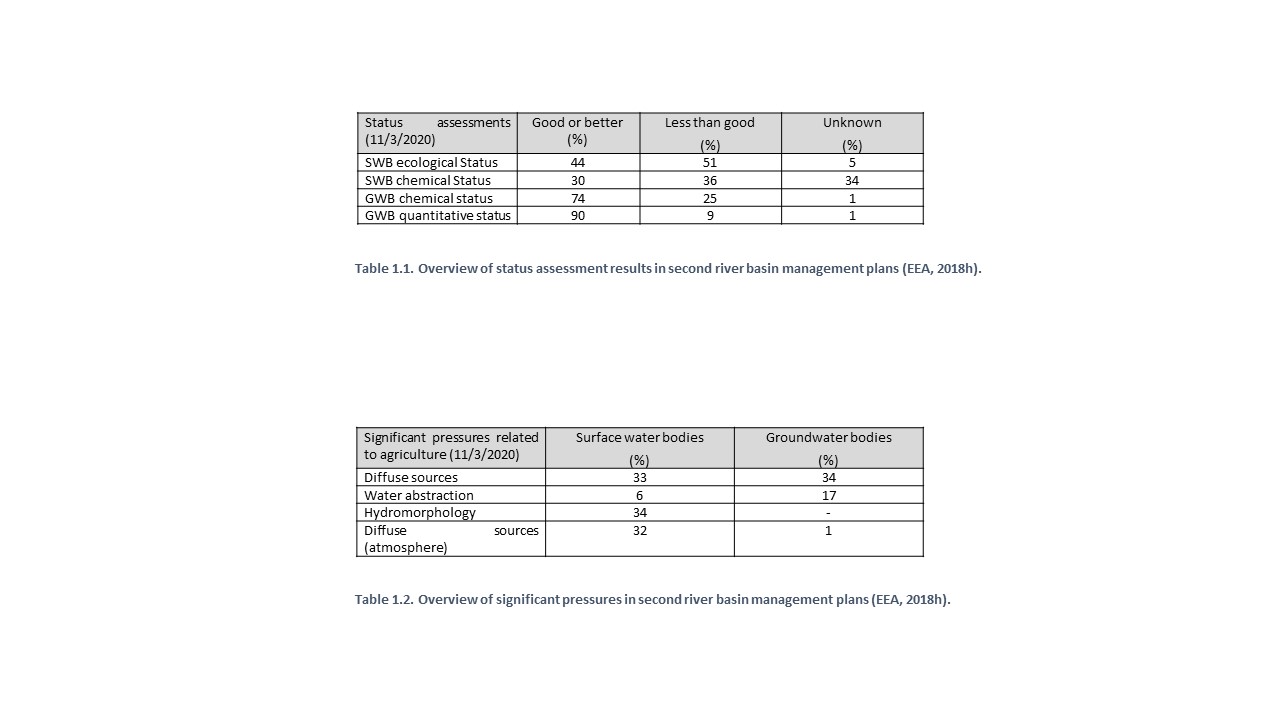

1.1 Towards good status in Europe’s river basins

The reporting of the 2nd river basin management plans under the Water Framework Directive showed 44% of EU-27, United Kingdom and Norway’s surface water bodies to be in good ecological status or potential, 30% to be in good chemical status, and 74% and 90% of groundwater bodies to be in good chemical and quantitative status respectively (Table 1.1). The second river basin management plans also showed that about one third of EU-27, United Kingdom and Norway’s water bodies were subject to significant pressures from diffuse sources, and hydromorphology, whereas 6% of surface water bodies and 17% of groundwater bodies were subject to significant pressures from water abstraction (Table 1.2). It is these pressures that need to be reduced to achieve improved status of water, a process that in many cases is complex as each water body can be subject to multiple pressures. In general, the proportion of water bodies in good status is lower, and the share of significant pressures is greater if only EU-27 is considered.

Agriculture is a major contributor to these pressures. Pressures from agriculture on the aquatic environment are linked to specific farming practices, especially those linked to crops: use of nutrients and water to promote plant growth and pesticides to avoid pests and diseases. The livestock production adds a major Furthermore, a wide range of hydromorphological changes have been made to improve conditions for crops but impacting habitat quality in the vicinity of rivers. As climate changes many of these pressures are anticipated to get worse with increased temperatures and water scarcity. Additional impacts on the agricultural production could become considerable.

In the report, the results of the river basin management plan assessments have been supported by a spatial analysis of indicators of agricultural pressures to show the extent of agricutural pressures on water across Europe. Indicators include nitrogen surplus, impact of pesticides, water abstraction and a proxy for hydromorphological pressures, at the scale of functional elemental catchments. These have also been combined into an overview of the cumulative pressures.

Furthermore, pressures from climate change may have considerable additional impact on the agricultural production. Climate change is already influencing availability of water for agriculture by altering the precipitation regimes and by increasing evapotranspiration from agricultural soil although positive effects on agriculture are also experienced due to increased temperatures and prolonged vegetation periods (EEA, 2019a). In the absence of adaptation to climate change, it is expected that major changes in the European agricultural production will take place. Agriculture is one of the most vulnerable sectors and will need to adapt to future climate impacts in order to sustain the level (quantity and quality) of production.

1.2 Global change and planetary boundaries

Since WWII, Europe has experienced unprecedented economic growth and prosperity, and together with this a very large growth in agricultural outputs, delivering a high diversity of food at affordable prices across Europe. Unfortunately, this has been at the expense of the environment. In the same period the intensification has been driven by nutrient, pesticides and irrigation water inputs, while very large areas have been drained to increase land area available for agricultural production.

Research increasingly reveals a clear human and climate impact on the global water cycle (Rodell et al., 2018). Ecosystems worldwide are impacted by the emission of nutrients and chemicals from agriculture. Globally, agricultural irrigation exacerbate water stress and lead to groundwater depletion. Recurrent water stress occur in many regions such as the central and western U.S., Australia, India, Pakistan, North‐East China and the Sahel.

Today several global planetary limits have been surpassed partially as a consequence of the agricultural production, the altered habitats have led to large declines in biodiversity, and climate change is increasing the uncertainty around critical climatic conditions. For example, phosphate fertiliser is based on a rare mineral, and climate change projections are pointing to larger areas subject to more frequent droughts, reducing water availability also in Europe.

At the same time the global challenge is to feed a population growing from 7.8 billion in 2007 to 9.6 billion in 2050, but without undermining the environment and resources on which food production depends, or jeopardizing food security which encompassing available, affordable, and safe food. To achieve this, more resilient farming systems are needed, i.e systems that are more diverse and require fewer resource inputs.

1.3 Policy context

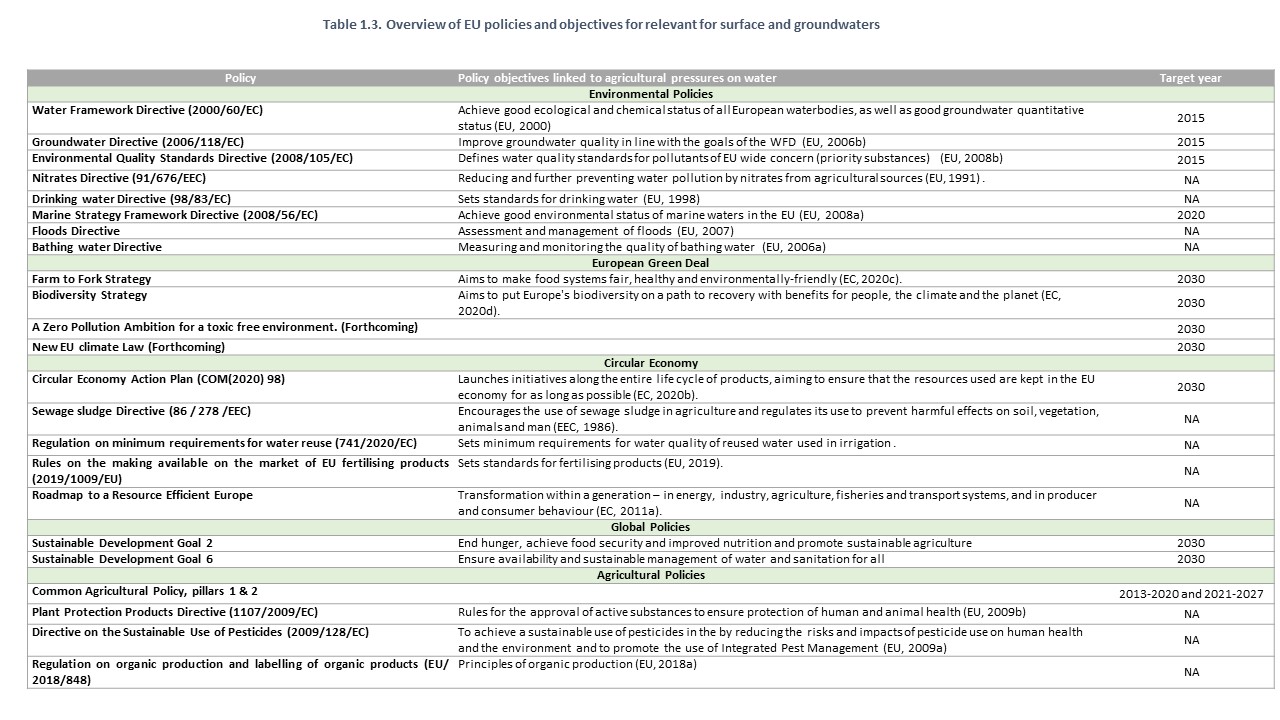

Against this background we describe the system for regulating environmental pressures from agriculture at European level. Agricultural pressures on the water environment is the object of an elaborate set of environmental policies, regulation and standards in Europe. In this regard, particularly important policies are the Nitrates Directive with its standards for nitrogen use in agricultural areas and the Water Framework Directive which requires achieving good ecological and chemical status of surface waters, and good chemical and quantitative status of groundwaters are particularly important. The Marine Strategy Framework Directive builds on the objective of the Water Framework Directive, in particular by requiring that nutrient and chemical pollution is not extended into the sea. These Directives are supported and reinforced by other Directives such as the Environmental Quality Standards Directive, the Groundwater Directive and the Drinking water Directive. Table 1.3 provides an overview of EU policy objectives for surface and groundwater bodies.

The watershed represents a fundamental unit for surface water. Within it, water quantity can be accounted for. Watershed land use activities linked to agriculture, forestry, or urbanisation, influence hydrology, nutrient and pesticide inputs, sediment input, and landscape properties all have the ability to change conditions in rivers, ultimately affecting one or more of the four status objectives of the Water Framework Directive. This inter-connectedness underlines the importance of considering a watershed as a whole.

This is fully recognised under the Water Framework and Floods Directives; their objectives are managed within river basins which are related to watersheds. Across Europe (EU-27 and UK), roughly 180 river basins have been identified, and for each river basin, a management plan has been developed. The river basins, however, follow national boundaries, sometimes dividing large watersheds into multiple national units. For accounting purposes, watersheds have also been divided into a system of progressively smaller basins, sub-basins and functional elemental catchments (FEC’s) (EEA, 2019h).

The Water Framework Directive and Marine Strategy Framework Directives require management plans and programmes of measures that reduce these pressures. Achieving those reductions, however, requires consideration of the close link between pressures and the uptake of good agricultural practices. In contrast, the interests of Europe’s farmers go beyond environmental protection. They also include securing income and livelihoods of Europe’s 10 million farms.

Different elements of the Common Agricultural Policy seeks to address those interests, including support to environmental objectives. In 2014-2020 around 38% of the overall EU budget was used for the EU Common Agricultural Policy (EUR 408 billion). Pillar I (74%) primarily consists of direct payments to farmers securing their stable income and consumers with a stable food supply at affordable prices. Pillar II (23%) is implemented through national rural development programs with a more diverse portfolio of objectives, aiming to improve competitiveness of farming and forestry, to protect the environment and countryside, improve the quality of life and diversification of the rural economy, and support locally based approaches to rural development. More specifically the three stated long-term rural development objectives are fostering the competitiveness of agriculture, ensuring sustainable management of natural resources and climate action and achieving balanced territorial development of rural economies and communities including the creation and maintenance of employment. In the 2014-2020 period Member States allocated around EUR 80 billion in rural development plans for restoring, preserving and enhancing ecosystems related to forestry and agriculture, increased efficiency in water use, and reduced greenhouse gas emissions and carbon sequestration from agriculture.

This funding is relevant because the pressures from agriculture on the environment are linked to specific farming practices, especially those linked to crops: use of nutrients and water to promote plant growth and pesticides to avoid pests and diseases. Furthermore, a wide range of hydromorphological changes have been made to improve conditions for crops but impacting habitat quality in the vicinity of rivers. The production of animals impacts the aquatic environment, especially because animal manure is used as fertiliser, but also because a significant proportion of intensive crop production aims to produce feed. Hence, the specific farming activities have a decisive impact on the aquatic environment. The specific choices made by farmers in terms of crops grown, animal production, and the details of how resources are used in the production all contribute to the environmental impact. Reducing environmental impact also means managing the choices of around 10 million farmers in Europe.

A recent study by the European Commission on the impact of the Common Agricultural Policy on Water (EC, 2020e), drew a number of important conclusions in regards to the current system:

- It was extremely difficult with the data and information available to the assessors to actually pinpoint the effectiveness of policies.

- Cross-compliance instruments (links to ND and WFD and standards for good agricultural conditions of land) target buffer strips, authorisation of water abstraction and discharge of dangerous substances, but member states usually settle for minimum standards

- Although, indirect, greening measures (crop diversification farm biodiversity and carbon sequestration) support achieving water objectives but were not ambitious enough to achieve significant changes in farming practices and hence guarantee the continuation of minimum beneficial practices

- The Common Agricultural Policy is the most important fund for achieving WFD objectives, but inconsistencies arise in the specific implementation, preventing the desired environmental improvements from taking place

The study and its conclusions is important in terms of understanding shortcomings of the 2014-2020 period. However, its analysis also stays within the boundaries of existing policies, it does not address areas for which policy is not in place although they may be important for achieving better solutions.

1.4 Towards a systemic perspective on water and agriculture

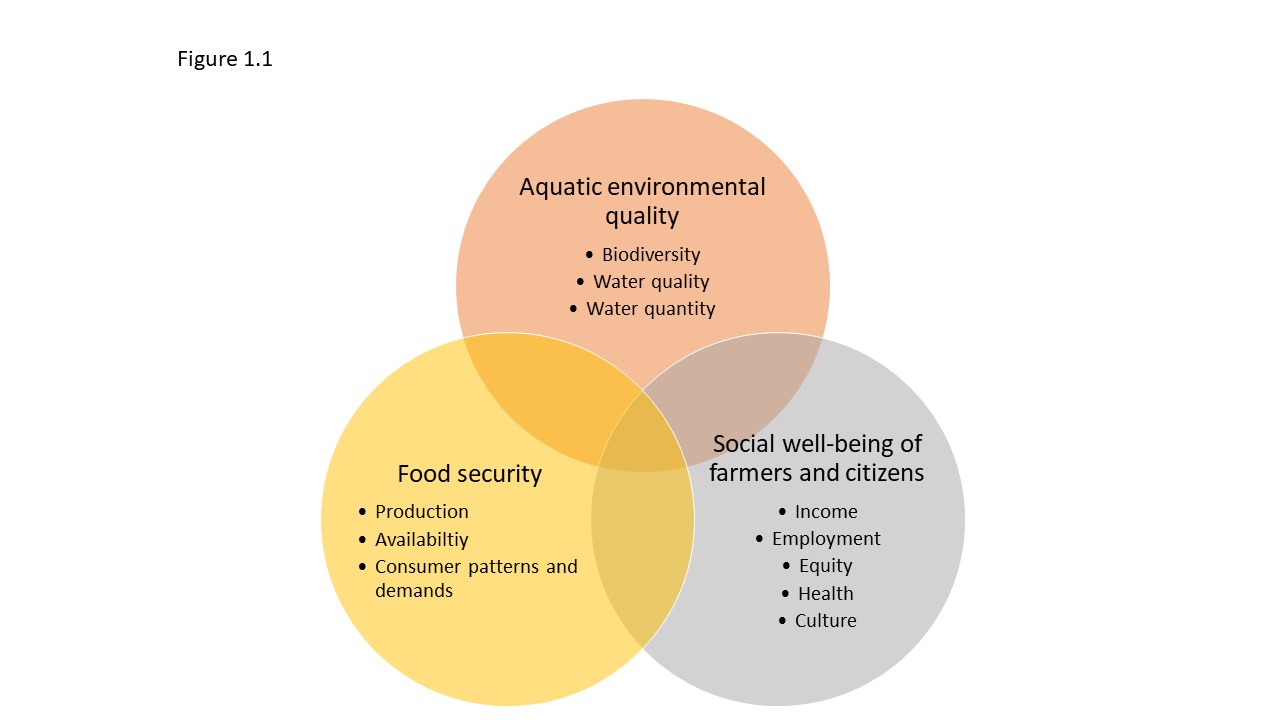

In its 5-yearly flagship report, the European Environment State and outlook 2020, the EEA highlighted the need to take a systems approach to respond to sustainability challenges. Agricultural production is a central component of the food system (Figure 1.1) and also the energy system, for instance with the production of bioenergy, and other bio-products. While improvements towards good status are possible through uptake of good farming practices, additional and possibly more fundamental changes can be made by tackling these consumption systems, and addressing some of the indirect drivers on agricultural production.

A sustainable food system is based on three interdependent pillars: the environment, food security, and the social well-being of farmers and consumers alike. Long term sustainable development requires the three pillars to be balanced. The system cannot be considered sustainable if food production takes place either at the expense of the farmer and consumer well-being or the environment.

The importance of food and other consumption systems in reaching sustainability is increasingly recognised in Europe. The recent Farm to Fork Strategy for instance attempts to achieve this by influencing consumer preferences towards choices that are more environmental and climate friendly. Studies have shown that environmental pressures could be reduced and human health improved considerably if consumer preferences for meat and dairy products were reduced by 50% (Westhoek et al., 2014).

Food security and sustainable agriculture are key challenges globally and for the European Union. By 2050, the global population is anticipated to have grown to 9.6 billion and delivering enough food in the light of a globally changing climate and environmental resource constraints is likely to become one of the major challenges of the 21st century, also in Europe. In Europe and globally, the food system continues to have a key role in supporting European societies, but it also has substantial environmental impact. This report explores in more depth the role of food systems in creating pressures and potential systemic responses.

1.5 Outline of report

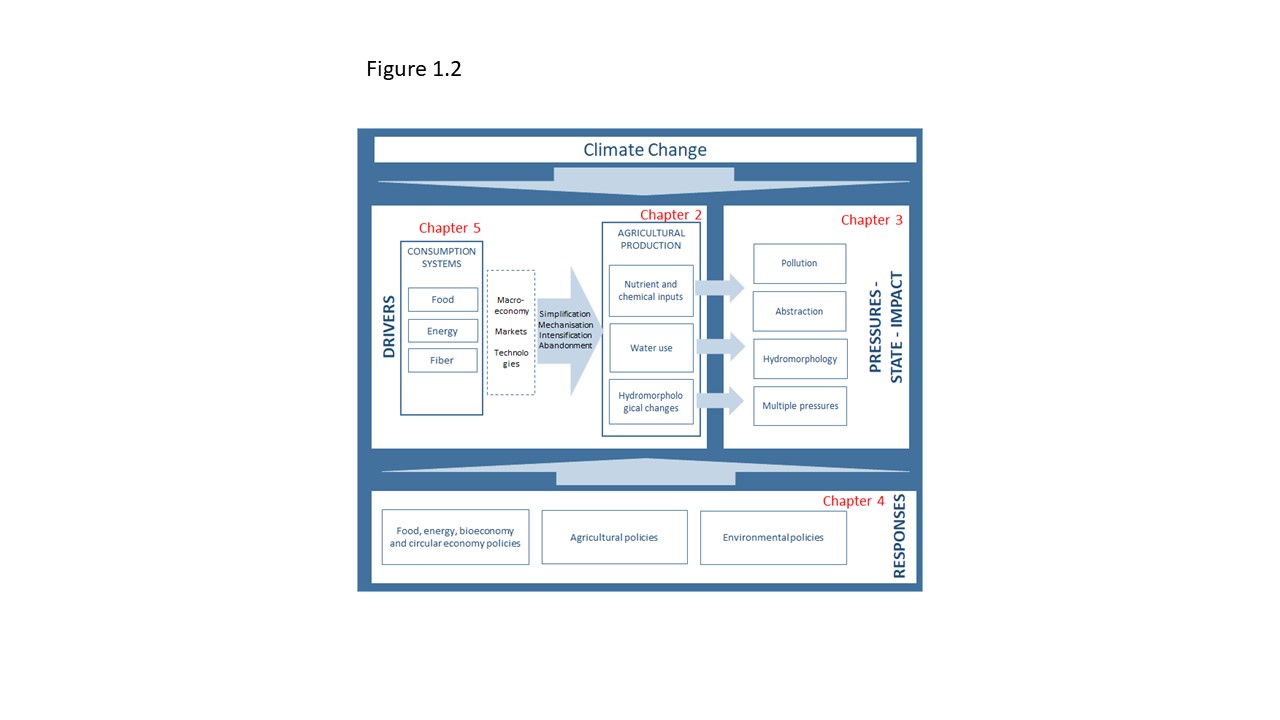

This report has been organised around a drivers-pressures-state-impact-response (DPSIR) approach to characterise the linkages between agricultural production, pressures on the water environment, their impact on the water environment, and management and policy responses (Figure 1.2). In addition, drivers on agricultural production were expanded to include not only direct drivers of pressures from agricultural practices but also indirect drivers stemming from consumption systems. Chapter 2 provides a brief overview of some characteristics of the agricultural sector, and discusses the intensification that has occurred in the second half of the 20th century. Chapter 3 provides an overview of pressures stemming from the agricultural production. Chapter 4 highlights how policy is responding to these pressures, and also characterises aspects of more resilient agricultural practices, and in chapter 5 we discuss the role of the overall food system in driving a more sustainable food production.