Table of contents

- General comments

- List of abbreviations

- Glossary

- Key messages

- Executive Summary

- 1. Introduction

- 2. Policy on water scarcity and drought

- 3. Impacts of climate change on water availability

- 4.Freshwater consumption in Europe under socio-economic change

- 5.Water stress in Europe

- 6.Needs for integrated policy responses

- 7.Conclusions

- References

- Annex : Recent EU innovation projects for water stress management

2. Policy on water scarcity and drought

- The WFD provides a flexible and suitable frame for action against water scarcity and drought, underscoring the relation between water quantity, water quality and ecological status.

- Despite the publication of the EU’s Communication on water scarcity and drought in 2007 and the Blueprint to Safeguard Europe’s Water Resources in 2012, EU policy on water scarcity and drought remains scattered and implementation has been slow.

- In the second RBMPs, sixteen Member States reported that water abstraction is a significant pressure for their surface water or groundwater at least in some parts of their national territory. However, only eight Member States reported DMPs as accompanying documents to all or part of their RBMPs whereas only three Member States developed ecological flows in all water bodies.

- The European Green Deal, the new Circular Economy Action Plan and the upcoming new EU Strategy on Adaptation to Climate Change represent fresh opportunities to integrate water stress and drought policy objectives into other areas, increase coherence and proper implementation.

2.1. Context: water scarcity and drought in EU water policy

Water stands amongst the oldest and most advanced policy areas in the EU environmental acquis (Josefsson, 2012; Giakoumis and Voulvoulis, 2018). Since 2000, the EU Water Framework Directive – WFD (2000/60/EC) is Europe’s flagship legislation on water, under which the wide variety of EU regulatory instruments, strategies and policy mechanisms that have emerged and evolved over decades are coordinated. Under the WFD, the EU has set an overall aim to “ensure access to good quality water in sufficient quantity for all Europeans, and to ensure the good status of all water bodies across Europe” (EC, 2000). Article 1 of the WFD requires the Member States to "promote the sustainable use of water resources based on the long-term protection of available water resources" and "ensure a balance between abstraction and recharge of groundwater, with the aim of achieving good status of groundwater bodies". Through these requirements the WFD sets the basis for action against water stress and drought, and it underscores the relation between water quantity, water quality and ecological status. The Fitness Check of EU Water Legislation also concluded that the WFD provides a flexible and suitable frame for the planning and management of drought risk and the impacts of water scarcity events (EC, 2019f).

The management of water stress across Europe has traditionally focused on supply-side measures, while drought management has been characterized by crisis management measures. Driven by shifts in the study of vulnerability and risk that originated in the 1980s (Vargas and Paneque, 2017), and underpinned by global developments like the Yokohama Strategy for a Safer World (UN, 1994) and its successors, the last three decades have increasingly seen the adoption of strategies that shift the focus more on water demand management. In addition, there is increased emphasis on the need for a more proactive risk management approach against droughts, calling for a drought management approach articulated around the aspects of preparedness, crisis management and resilience building.

Box 2.1 Important terms

Preparedness: long-term water resources monitoring to evaluate the water-related risks and corresponding planning to manage effectively the anticipated water deficits, considering also the risks from probable drought events.

Crisis management: activation of pre-defined emergency plans and measures to deal with critical water deficits during the occurrence of drought events.

Resilience building: development of the necessary knowledge base, awareness, governance structure and technical infrastructure to support preparedness and crisis management against drought risks (e.g. raising awareness on water security concerns; providing capacity building and training; climate-proofing of socio-economic activities and areas; employing nature-based solutions for climate change adaptation; integrating ecosystem services in finance and insurance schemes dealing with water scarcity and droughts)

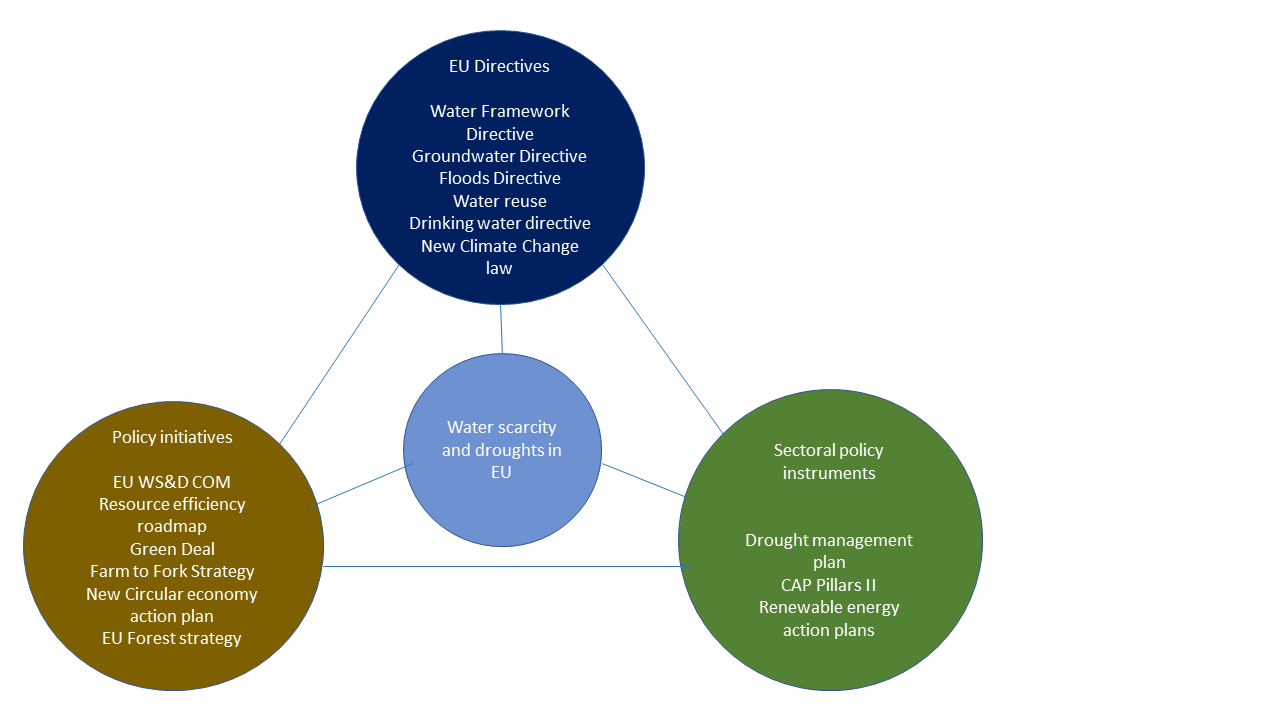

Overall, EU policy for water scarcity and drought has evolved around three supplementary pillars: EU directives (e.g. Water Framework Directive, Groundwater Directive, Floods Directive), policy initiatives (e.g. Communication on Water Scarcity and Drought, Circular Economy Action Plan, Resource Efficiency Roadmap) and sectoral policy instruments (e.g. Pillar II of the CAP and Regional Environmental Policy) as shown in Figure 2.1.

The WFD itself establishes, at river basins scale, an integrated planning framework to enhance protection and improvement of the aquatic environment with the final goal of achieving the good environmental status of European waters. A key product of the WFD planning process is the River Basin Management Plan (RBMP), which is accompanied by a relevant Programme of Measures (PoM). The WFD recognizes the crosscutting character of water as a vital resource for social, environmental and economic systems, which places water policy in the middle of developments in other policy areas. To tackle water stress and droughts, the WFD puts more importance on acting on the drivers underpinning water demand (i.e. reducing demand from economic sectors consuming water) than increasing water supply. The WFD encourages abstraction control through permitting, water demand management, and efficient water use. However, supply-oriented measures, including reservoirs or diversions (inter-basin transfers), have also been planned in recent years by several Member States to meet their concerns on water security or shift their local water supply to alternative sources, because of the depletion and degradation local groundwater (Buchanan et al., 2019).

Nevertheless, despite their overall alignment with the above policy lines, several EU Member States (e.g. France, Greece) have reported their intention to further construct supply-oriented measures, such as reservoirs or diversions (inter-basin transfers), because they consider (whether or not correctly justified) that these measures could contribute to various goals, including water and energy security, adaptation to climate change, achievement of ecological flows in water-stressed aquatic ecosystems and protection of over-exploited groundwater bodies from further deterioration

In 2007, the European Commission published its Communication on Water Scarcity and Drought (EC, 2007), which outlines seven concrete policy options to address water scarcity and drought at European, national and regional levels:

- Putting the right price tag on water

- Allocating water and water-related funding more efficiently

- Improving drought risk management

- Considering additional water supply infrastructures

- Fostering water efficient technologies and practices

- Fostering the emergence of a water-saving culture in Europe

- Improve knowledge and data collection

The Communication calls for a “water efficient and water saving economy” that integrates “water issues into all sectoral policies”. There is an explicit recognition that economic development, in the form of e.g. new urban areas, industrial production capacities or irrigation perimeters, must take into account the availability of local water resources in order to avoid exacerbating water stress and the risk of damaging droughts. The implementation of the policy options promoted by the Communication was assessed in three yearly follow-up reports and a policy review (EC, 2008, 2010b, 2011b).

Two additional policy documents have since been published addressing water stress and droughts (Figure 2.2):

- The Blueprint to Safeguard Europe’s Water (EC, 2012) re-emphasized the need to take action against scarcity and droughts. It integrates a particular focus on the need to increase resource use efficiency and decouple growth from resource use, drawing on the Resource Efficiency Roadmap 2011 (EC, 2011a), and recently reemphasized in the new Circular Economy Action Plan (EC, 2020a) under the EU Green Deal (EC, 2019j).

- The EU Strategy on Adaptation to Climate Change (EC, 2013a), first published in 2013 and to be updated in 2021, served to establish reference points and define new aims on increasing climate resilience and disaster preparedness. In water management, this has closely linked with efforts in improving drought risk management under the 2007 Communication and preparation of Drought Management Plans (DMPs) by Member States.

Figure 2.2 Timeline showing major policy developments related to water scarcity and drought since the adoption of the WFD.

Undertakings at the EU level have resulted in achievements in the form of research, policy options, and technical guidance to deal with water scarcity and drought (Hervás-Gámez and Delgado-Ramos, 2019). However, the EU policy approach towards water quantity has generally been less elaborate than it has been for water quality (Stein et al., 2016; Eslamian and Eslamian, 2017; Trémolet S. et al., 2019), and the pace of change in this specific policy area has been slow.

Developing comprehensive and incentive regulatory frameworks and pricing mechanisms is equally important as developing the necessary technical solutions to facilitate the uptake of new technologies (Buchanan et al., 2019). Recently, general considerations on water stress have been integrated in the EU Green Deal, as evidenced by the Biodiversity Strategy for 2030, the Farm to Fork Strategy, the 2030 Climate & Energy Framework, the new Circular Economy Action Plan and the 2050 Long-term Strategy. Elements of water security and insurance are also now embedded in the EU’s Sustainable Finance Taxonomy. The challenge will continue to be the transposition of these principles and provisions at the operational level.

To this date, the management of water stress remains largely a national policy, but it operates within a multi-level governance scheme where different administrative levels play distinct roles. In keeping with the subsidiarity principle, the WFD and EU water scarcity and droughts policy provide a frame to integrate and build up on the Member States’ knowledge of local conditions while avoiding that short-term regional or local interests put the future needs of the wider community at risk. This effectively means that the EU complements the regulation and management responsibilities of local and regional authorities (EU COR, 2011). Nonetheless, there could be cases where the responsible public administration fails to develop a long-term strategy looking beyond the 6-year management cycles of the WFD and building effectively on the RBMPs (Buchanan et al., 2019).

On the one hand, authorities and stakeholders in many Member States have scaled up collaboration in planning and management, leading to greater policy integration of water stress issues at local and regional level. This triggered action from some Member States, and the latest DMPs have been accepted in 2018. The compliance assessment of the second RBMPs (EC, 2019b) showed that sixteen Member States reported water abstraction as a significant pressure for their surface water or groundwater at least in some parts of their national territory([1]). However, only eight Member States reported DMPs as accompanying documents to all or part of their RBMPs([2]). Furthermore, the content of these plans and the depth of the analysis differ greatly among Member States, despite the existence of a relevant technical report on the development of DMPs([3]). Cyprus and Spain are two cases with very detailed and comprehensive DMPs accompanying their RBMPs. Some elements of these plans are regarded as novel and promising (Hervás-Gámez and Delgado-Ramos, 2019).

On the other hand, it should be noted that progress in implementation has been slow since the Blueprint to Safeguard European Waters back in 2012. The transition from crisis to risk management approaches has been mostly a conceptual one, as in its implementation, this change of paradigm has exposed a lack of institutional capacity across many Member States (Tsakiris, 2015). Further, to be truly effective, the risk management approach has to be adopted by all sectors which have a direct or indirect influence on water, e.g. via decisions on land use (EU COR, 2011). It will be important to renew the efforts on this, especially in areas with recurrent drought issues, as the impacts of temporary drought events can last much longer than the initial phenomenon and their socio-economic damages can be considerable. The EU Green Deal and the update of the EU Strategy on Adaptation to climate change are opportunities to do so.

Between the first and second WFD planning cycle, water pricing has been more widely applied by EU Member States, and new pricing schemes were introduced in various sectors (e.g. drinking water & sanitation, agriculture, industry). However, although incentive pricing is an explicit requirement of the WFD to ensure compliance with its principles and objectives, the current pricing mechanisms do not always provide adequate incentives for efficient water use and sustainable water management (Buchanan et al., 2019).

Furthermore, the key reason for delays in the implementation of measures tackling water stress is usually the lack of secure budgets. Measures can rely largely on the public budget, whereas the capacity of EU funds is not always fully exploited (Buchanan et al., 2019). The coordination of the European Common Agricultural Policy (CAP) and the Rural Development Plans (RDPs) is a good example here, as highlighted by EEIG Alliance Environnement (EC, 2020d).

Finally, the lack of robust governance on water stress at EU level has left ample space for discrepancies between Member States in interpretations, and drought policy has important limitations regarding compliance (Stein et al., 2016). For example, most Member States apply exemptions from registration or permitting for water abstractions considered to be “small”([4]) in volume. Overall, the accumulation of all these small abstractions over a large area could result in a significant pressure (e.g. for local groundwater bodies), which is disregarded. Similarly, in some areas, there are issues with over-allocation of water rights which were issued before the adoption of the WFD. Although the WFD has provided a significant motivation for local authorities to review the pre-existing water rights, and revise them according to the identified over-exploitation problems, Member States usually have difficulties to intervene with permits that were granted a long time ago and the so-called “senior water rights”. As a result, most Member States have become stricter with issuing newer water permits (EC, 2020d; Buchanan et al., 2019).

Combined, these barriers slow down progress in the achievement of the WFD’s objectives and limit the ambitious implementation of EU WS&D policy. There is thus a continued need to address issues like policy integration, coherence and compliance (EC, 2020d, 2015d).

2.2. Sectoral policy responses and their links to water stress

Beyond the dedicated water policies which have been the main focus of this chapter so far, a wide range of sectoral and environmental strategies, instruments and measures are in places which directly or indirectly address the impacts of water stress and drought. These include policies in the fields of agriculture, energy, industry, transport, biodiversity, nature protection and climate change.

The EU Green Deal has largely managed to encapsulate global developments advocating systemic change, and its ongoing action plan intends to enable deep transitions in Europe. The strategy recognises the need to “restore the natural functions of ground and surface water” and tackle the “excessive consumption of natural resources”. It sets out a number of industry reforms aligned to foster the transition towards circularity, and towards a greener and resource-efficient economy. At a macro-level, the Green Deal aims to increase sustainable finance and channel public and private investments into sustainable activities and projects. The use of crosscutting instruments such as the EU Sustainable Taxonomy is highlighted in the Green Deal, as they aim to establish financing standards to increase efficient use and protection of –among others- water resources across the European economy.

Agriculture is the sector with the largest demand for water, and also one of the worst hit in the recent drought events of 2018 and 2019. Relevant impacts for the sector include loss of crop yields and harvested production; increased costs for water supply and irrigation; and heightened potential for tensions, disputes and even conflict with competing users. The sector’s flagship policy, the CAP, is undergoing a reform process that includes among its aims a readjustment of its focus to incorporate better water management into farm practices. Under the Rural Development Regulation, also known as Pillar II of the CAP, a set of measures including training and farm modernisation to promote water efficiency are concrete elements widening the scope of the agricultural practice to include environmental protection and improvement.

In the energy sector, common impacts include decrease of energy production in thermal plants due to low river discharges (and reduced access to cooling water); decrease of electricity production in hydropower plants due to low reservoir levels, and increased electricity prices. The EU Commission’s reiterated commitment to achieve climate neutrality and fully decarbonised power generation by 2050, with 80% of the union’s power generated from renewable sources, opens expectations for future changes in the sector’s water demand. Links to water stress in the Renewable Energy Directive (EC, 2009) and the EU’s Energy Union Strategy (EC, 2015a) are indirect and mainly stem from integrated climate and energy planning and monitoring of greenhouse gas emissions. The more recent EU Strategy for Energy System Integration 2020 (EC, 2020c) includes considerations on the water footprint of EU energy production and the potential for sustainable production of bioenergy from wastewater.

The industrial sector includes manufacturing operations as well as mining and quarrying, which are in many cases activities associated with high water demand levels. Impacts of imbalances in water availability include restrictions on production plans and even plant shutdowns in highly water-dependent operations. Policy responses in this sector have focussed primarily on resource efficiency and circularity approaches and include the Resource Efficiency Roadmap (EC, 2011a) and the Circular Economy Action Plan from 2015 (EC, 2015b)which was recently updated (EC, 2020a)under the EU Green Deal (EC, 2019j). The New Industrial Strategy for Europe (EC, 2020b)that surfaced in March 2020 does not include any clear references to water quantity issues.

Lastly, the transport sector can also be significantly impacted by water scarcity and drought events. The 2018 drought caused restrictions for inland navigation in Central Europe and disrupted supply chains along entire river basins.

These are just some examples of the main sectoral impacts and measures that give insight into the importance of concerted and coordinated action beyond sectoral silos.

Worldwide, there is growing awareness of the need for policy responses that address the impacts of climate change on water (Quevauviller and Gemmer, 2015). In Europe, climate change and population growth are shifting conditions across a wider geographical spread (see Chapter 3). Member States like Sweden and Germany have suffered great economic losses stemming from droughts in 2018 and 2019, and increased variability in weather patterns is making the existing hotspots (e.g. Southern Europe) worse off. This is drawing renewed attention to water availability issues at the EU level, once more calling for updates on water scarcity and drought policy and action.

Regarding the consideration of climate change in the second RBMPs, significant progress was achieved compared to the first cycle. Most Member States used the CIS Guidance Document (EC, 2009) and climate change was integrated in a series of actions related to the preparation of the RBMPs. However, there are still large gaps to address before climate change can be considered fully integrated. In addition, eight Member States reported the planning of specific measures to address Climate Change Adaptation (CCA). Various Member States have also reported multi-purpose measures, which could be relevant in the context of climate change adaptation, although this is not explicitly stated (Buchanan et al., 2019; EC, 2019g).

The current EU Climate Change Adaptation Strategy aims to build capacity and increase resilience to extreme weather events, including droughts. In this regard, there have been explicit calls and efforts to explore and further develop adaptation solutions that incorporate natural elements in them, such as green infrastructure and nature-based solutions. Commonalities between EU adaptation policy, the EU Strategy on Green Infrastructure and the Biodiversity Strategy to 2030, represent another interface between policy areas where water plays a central role. Here, progress has been made on the study of natural water retention measures that enable the achievement of multiple objectives like increasing drought resilience and water security, reducing habitat fragmentation, decreasing the emission of greenhouse gases, and providing spaces for recreation. Nevertheless, the primary objectives behind the construction of natural water retention measures are currently flood risk management, nutrient buffering and wastewater treatment, hydromorphological restoration and biodiversity protection (Buchanan et al., 2019). Water quantity and climate change adaptation objectives seem to be less influential in motivating their application. The Mission area on Adaptation to climate change underpinning the EU’s Horizon Europe research programme and the update of the EU Climate Adaptation Strategy are expected to drive more ambitious adaptation action through the funding of applied research and innovation and the demonstration of new solutions, including nature-based ones.

2.3. Policy developments at the global level

To tackle water scarcity and drought, the international community has recognized the need for an integrated approach between water, energy, food and ecosystems (EC, 2019i). The approval of the UN 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development (UN, 2015b) invigorated the discussion on systemic change that permeates recent EU policy, highlighting the importance of collaboration and policy integration and coherence. The own nature of the SDGs is crosscutting and calls for joint implementation. As to their coverage of water stress issues, SDG 6.4 highlights the need to increase water use efficiency across all sectors and decoupling economic growth and water use and SDG 6.5 promotes integrated water management. Key sectors include agriculture, energy, industry and public water supply. This makes the WEFE (Water, Energy, Food, Ecosystem) Nexus approach suitable for the pursuit of the SDGs. WEFE Nexus assessments and projects are gaining traction around the world, and the underlying principles of the approach can also be identified in the most recent EU policy developments. The collective experience gathered by these projects could become instrumental in resolving known issues regarding the differentiation between concepts (e.g. water abstractions and water use) and the inclusion of environmental flows in the development and reporting of the indicator group on SDG 6.

From a climate resilience perspective, the previously mentioned paradigm shift on vulnerability and risk is largely reflected today in the UN Sendai Framework for Disaster Risk Reduction. Since its publication in 2015, the global framework has leveraged a transition away from crisis management towards risk planning that was already underway in European countries like Spain since the 1990s. It has also been effective in creating a frame for international coordination on the management of hydrometeorological risks such as droughts. The Sendai Framework will remain in force until 2030, and in the context of the current climate crisis that raises citizen awareness but also emboldens Member States interest on implementing measures to increase water supply. It will also be an important lever to maintain the emphasis on addressing unsustainable water management and exploitation practices.

[1] Belgium, Cyprus, Greece, Denmark, Spain, Hungary, Italy, Malta, Portugal, Slovakia, UK, Bulgaria, Croatia, Czechia, Germany, France

[3] Expert Network (2008). Drought Management Plan Report - Including Agricultural, Drought Indicators and Climate Change Aspects. Technical Report 2008 – 023

[4] Perception and definition of “small” abstraction differs among Member States, e.g. France: 1,000 m3/year; Netherlands (indicative, varies per water board): 100 m3/h (registration is obligatory, but no permit required).