Table of contents

3. How do we care for bathing waters?

3.1 Control of bathing health risks through legislation

When bathing takes place outdoors, the need to protect and improve water quality is an issue both for human and environmental health. In other words, healthy aquatic ecosystems benefit both human and non-human lives. Bathing waters are thus sites where European environmental and public health policies overlap and support one another. It is for this reason that the concept of bathing water quality has been addressed in research, policy and legislation. From a global perspective, the term ‘bathing water’ is predominantly used in Europe and it is indeed here that the need to protect bathing environments was originally identified in the 1970s, and developed in subsequent decades. The World Health Organisation’s (WHO) activity that aims to foster safe bathing environments on a global scale is based on this European legacy, and the EU's Bathing Water Directive is based on the same concept.

Before the EU Bathing Water Directive was originally adopted in 1976, large quantities of mostly uncontrolled, untreated or partially-treated wastewater were discharged into many of Europe’s surface waters. As a result, these waters became heavily polluted. Dirty beaches and resulting concerns regarding the health of swimmers and growing environmental awareness consequently paved the way to the BWD’s adoption. European Member States were obliged to take all necessary measures to ensure that the quality of their bathing water conformed to water quality guidelines within ten years. These guidelines included 19 microbiological (i.e. several bacteria and viruses) and physico-chemical (i.e. pH, colour, presence of oils, concentration of dissolved oxygen etc.) parameters. Other substances regarded as indications of pollution, and potentially dangerous to public health were also included. The Bathing Water Directive is one of the great success stories of EU environmental policy, and the overall quality of bathing water across Europe has steadily improved since its adoption.

The initial Bathing Water Directive reflected the state of European populations, scientific knowledge and policy experience of the early 1970s. Patterns of bathing water use have changed since then, as has the state of scientific and technical knowledge. As a result, a revised version of the Bathing Water Directive (2006) came into force in 2006, addressing all surface water sites where a large number of people are expected to bathe during the season suitable for bathing. This designation does not include swimming pools, confined waters subject to treatment, or artificially created confined waters separated from surface water and groundwater. All EU Member States are subject to this legislation, whilst an additional two (Albania and Switzerland) are part of the European bathing water monitoring network. The revised BWD uses the latest scientific evidence in implementing the most reliable indicator parameters for predicting microbiological health risk for designated bathing waters, and simplifies its management and surveillance methods. The resulting information is presented to the public in a variety of interactive and accessible ways, allowing people to find clean bathing waters, and to receive timely notifications of water quality deteriorations and health risks.

-

-

We have now explained at the end of the paragraph. We are not mentioning the ambiguity that not all bathing waters in the EU are situated within the identified surface waterbodies.

-

However, with the BWD now fully implemented throughout the EU, it is important to continuously assess its results. It is not merely a case of assessing water quality across Europe, but also about encouraging various stakeholders – such as national politicians, environmental managers, tourism managers, bathing water managers – to integrally implement the Directive. How do we deal with an (albeit small) number of ‘poor’ quality bathing waters that are still attractive for swimming? How do we relate bathing water management with wider environmental issues? How do we make bathing safe in urbanised and once heavily polluted environments? And how do we work towards improving the quality of already ‘sufficient’ bathing sites so that they achieve ‘good’ or ‘excellent’ classification status? These are the questions addressed through the concept of integrated bathing water management discussed in this report.

Before the EU Bathing Water Directive was originally adopted in 1976, large quantities of mostly uncontrolled, untreated or partially-treated wastewater were discharged into many of Europe’s surface waters. As a result, these waters became heavily polluted. Dirty beaches and resulting concerns regarding the health of swimmers and growing environmental awareness consequently paved the way to the BWD’s adoption. European Member States were obliged to take all necessary measures to ensure that the quality of their bathing water conformed to water quality guidelines within ten years. These guidelines included 19 microbiological (i.e. several bacteria and viruses) and physico-chemical (i.e. pH, colour, presence of oils, concentration of dissolved oxygen etc.) parameters. Other substances regarded as indications of pollution, and potentially dangerous to public health were also included. The Bathing Water Directive is one of the great success stories of EU environmental policy, and the overall quality of bathing water across Europe has steadily improved since its adoption.

The initial Bathing Water Directive reflected the state of European populations, scientific knowledge and policy experience of the early 1970s. Patterns of bathing water use have changed since then, as has the state of scientific and technical knowledge. As a result, a revised version of the Bathing Water Directive (2006) came into force in 2006, addressing all surface water sites where a large number of people are expected to bathe during the season suitable for bathing. This designation does not include swimming pools, confined waters subject to treatment, or artificially created confined waters separated from surface water and groundwater. All EU Member States are subject to this legislation, whilst an additional two (Albania and Switzerland) are part of the European bathing water monitoring network. The revised BWD uses the latest scientific evidence in implementing the most reliable indicator parameters for predicting microbiological health risk for designated bathing waters, and simplifies its management and surveillance methods. The resulting information is presented to the public in a variety of interactive and accessible ways, allowing people to find clean bathing waters, and to receive timely notifications of water quality deteriorations and health risks.

However, with the BWD now fully implemented throughout the EU, it is important to continuously assess its results. It is not merely a case of assessing water quality across Europe, but also about encouraging various stakeholders – such as national politicians, environmental managers, tourism managers, bathing water managers – to integrally implement the Directive. How do we deal with an (albeit small) number of ‘poor’ quality bathing waters that are still attractive for swimming? How do we relate bathing water management with wider environmental issues? How do we make bathing safe in urbanised and once heavily polluted environments? And how do we work towards improving the quality of already ‘sufficient’ bathing sites so that they achieve ‘good’ or ‘excellent’ classification status? These are the questions addressed through the concept of integrated bathing water management discussed in this report.

3.2 Integrated bathing water management

Integrated bathing water management involves finding synergies between different parties and interest groups through collaboration to encourage effective bathing water management. Under this approach, bathing water designation should not follow a traditional top-down approach where a higher authority (e.g. the EU) delegates tasks to participants at lower levels (e.g. a local community). Public consultation and engagement with local communities is vital, and plays an important role when dealing with the challenges associated with bathing water management. Every European Member State tackles its own specific issues when managing bathing waters and implementing the BWD. These specifics depend mostly on physical, administrative, and socio-economical constraints (EEA, 2016b). Nevertheless, all Member States make great efforts, not only to improve the quality of existing bathing waters and provide up-to-date information to the public, but also to make bathing feasible in urbanised and formerly heavily polluted surface waters.

Clean water in freshwater ecosystems is not only beneficial for bathing: it also benefits drinking water provision and the wider health of the ecosystem. Efforts to improve bathing water quality therefore need to be closely coordinated with the suite of legislation designed to protect and manage European waters. These include the legislation on urban waste water treatment[1], drinking water[2], management of nitrates[3] in farming that affect water sources, protection of marine environments[4] and ultimately the Water Framework Directive (2000). These so-called ‘water industry directives’ focus on protecting human health, whilst at the same time regulating farming and economic practices as to reduce and prevent water pollution. Various elements of these policies focus on managing specific parts of the water cycle. Between them, there is a European monitoring and reporting network to document the quality of the water abstracted and used by humans2, discharged afterwards1, and the quality of the water available for recreational purposes[5] (EEA, 2016b). Efficient bathing water quality management therefore dovetails with the implementation of other European water policies. The Urban Waste Water Treatment Directive (UWWTD) regulates the collection, treatment and discharge of urban waste water, whereas the WFD regulates a holistic approach to maintaining good water status in general. Box 1 illustrates an example of how the implementation of UWWTD and WFD brought positive results in implementing the BWD at the Lacuisine bathing water on the Semois River in Belgium (Box 1).

-

In the paragraph “Clean water in freshwater ecosystems is not …” a reference to “water industry directives” is given wrongly. Water industry directives do not include the WFD and MSFD as those are “ecosystem directives”.

-

We have pephrased the paragraph to be more precise/clear.

-

An important aspect of European bathing water legislation is the involvement of all stakeholders around a water body, including the public. European legislation has thus also integrated the practices of the Blue Flag programme, started in 1985 by a non-governmental organisation. The programme seeks to implement various environmental, educational, safety, and accessibility criteria at bathing waters (EEA, 2016b). While the majority of Blue Flags have been awarded to coastal bathing sites, the number of blue flags on inland bathing waters, including in cities, is increasing.

-

Perhaps for the blue flag should be pointed out which is recognised at the specific request of the competent bathing water authority.

-

We have rephrased the paragraph in line with the comment.

-

Box 1: Successful water policy synergy: the case of Lacuisine (Belgium)

For many years, the Walloon Region in Belgium permanently prohibited bathing at the Lacuisine bathing water on the Semois River due to ‘poor’ bathing water quality. Such prohibition of (or advice against) bathing is prescribed by the BWD to protect human health and to encourage management of the underlying issues that affect environmental quality.

Between 2012 to 2016, numerous measures were undertaken in order to improve the quality of bathing water at Lacuisine. These included improved urban drainage, the construction of a wastewater treatment plant and a collector built in the upstream protection zone, the establishment of pasture bank fences in upstream area, and controlling storm water overflows on the bathing area. These measures were designed and implemented in the framework of the holistic approach provided by the WFD. Together, they worked to substantially improve the quality of water at Lacuisine.

After six years of water quality management, Lacuisine was re-opened for bathing in 2018.

Successful integration of bathing and urban waste water treatment legislation had also a positive effect on water quality at Ardmore Beach in Ireland (Box 2).

Box 2: Water policy integration: the case of Ardmore Beach (Ireland)

Ardmore Beach is a sandy beach on the south coast of Ireland near Ardmore village. It is visited by hundreds of bathers, surfers and kayakers during the bathing season. The biodiversity of the beach and its surroundings is relatively high. Between the beach and harbour, low tide provides access to rock pools which are home to numerous species of shrimps, crabs, fish, and anemones. Natural heritage areas situated in the vicinity of the beach include vegetated sea cliffs and coastal dry heather which are home to many bird species, and the Blackwater estuary, an internationally important wetland site.

During 2014, high tides and strong winds interfered with the normal dispersion and dilution of screened sewage from the nearest waste water treatment plant, causing bathing water to be classified as ‘poor’. In order to improve bathing water quality, water discharged from the treatment plant has been additionally treated during the bathing season. Bacterial levels were significantly reduced. Bathers, surfers and kayakers returned to the beach, as soon as the advisory notice was removed. For the past two years, bathing water at Ardmore beach has been of ‘excellent’ quality.

-

Congratulations on this draft report.

EPA Ireland have reviewed and have one comment to make in relation to 'Box 2: Water policy integration; the case of Ardmore Beach (Ireland)'. Would it be possible to amend the last sentence please from 'For the past two years, bathing water at Ardmore beach has been of 'excellent' quality.' with 'A new wastewater treatment plant for Ardmore village was commissioned in early 2016 and bathing water quality at Ardmore is now classified as 'excellent'.

Many thanks,

Brigid Flood

Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) Ireland

-

The proposal has been accepted - the last sentence has been amended as requested.

-

The bathing season in Europe usually lasts from May to September. During that time, local and national authorities take bathing water samples and analyse them for types of bacteria which indicate pollution from sewage or livestock (e.g. Escherichia coli and intestinal enterococci). Based on detected levels of bacteria, bathing water quality is then classified as ‘excellent’, ‘good’, ‘sufficient’ or ‘poor’. Polluted water can have negative impacts on human health – such as diarrhoea or stomach problems – if swallowed (EEA, 2018). According to the BWD, if bathing water quality has been ‘poor’ for five consecutive years, bathing must be permanently prohibited, or permanent advice against bathing must be put in place.

The next section will show how the quality of European bathing waters has improved in recent decades.

3.3. From polluted to excellent bathing waters

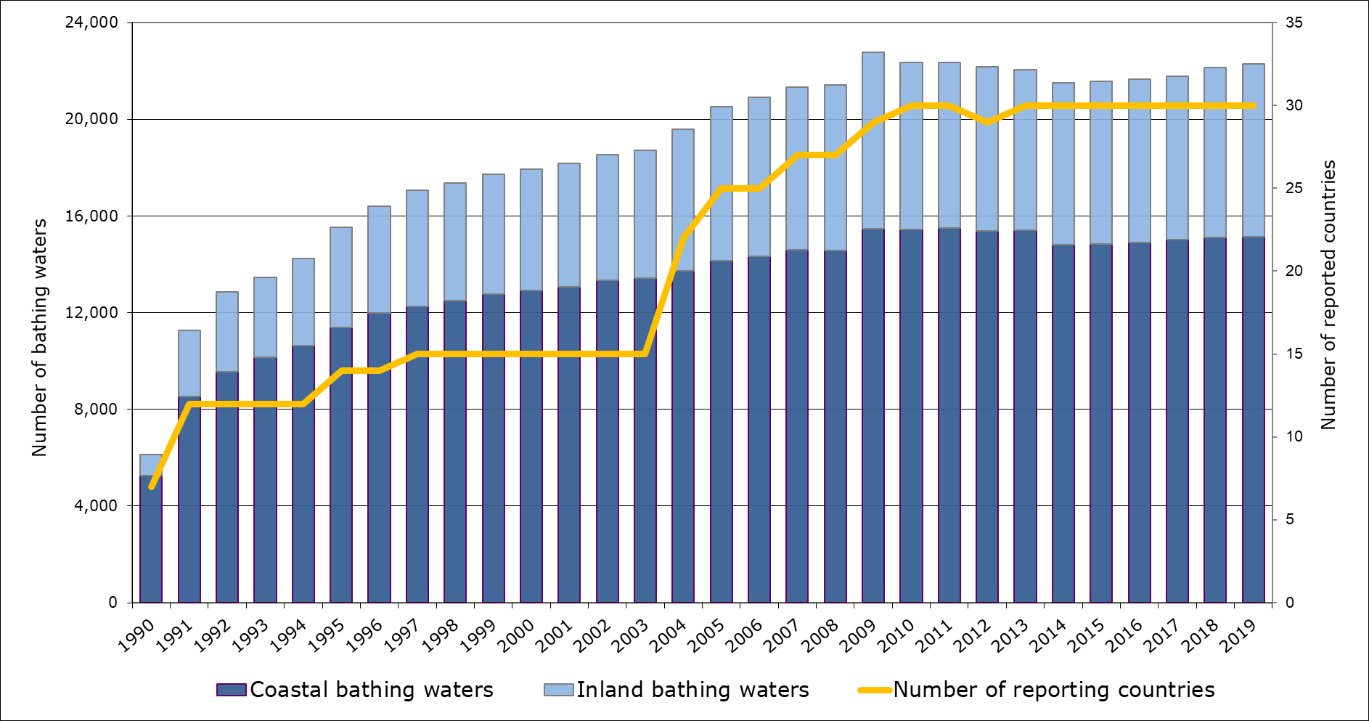

Over almost 30 years there has been an increase in the number of European bathing waters that are monitored and managed under the BWD. The increase was especially dramatic between 1990 and 1991: the number of bathing water sites monitored by seven EU Member States in 1990 was 7 539, while just a year later, there were five more Member States and the number of bathing waters increased to 15 075. Since 2004, bathing water quality has been monitored at more than 20 000 locations; in 2019 there were 22 295 official bathing waters in Europe (Figure 2).

Figure 2: Total number of bathing waters in Europe since 1990

Source: WISE bathing water quality database (data from annual reports by EU Member States).

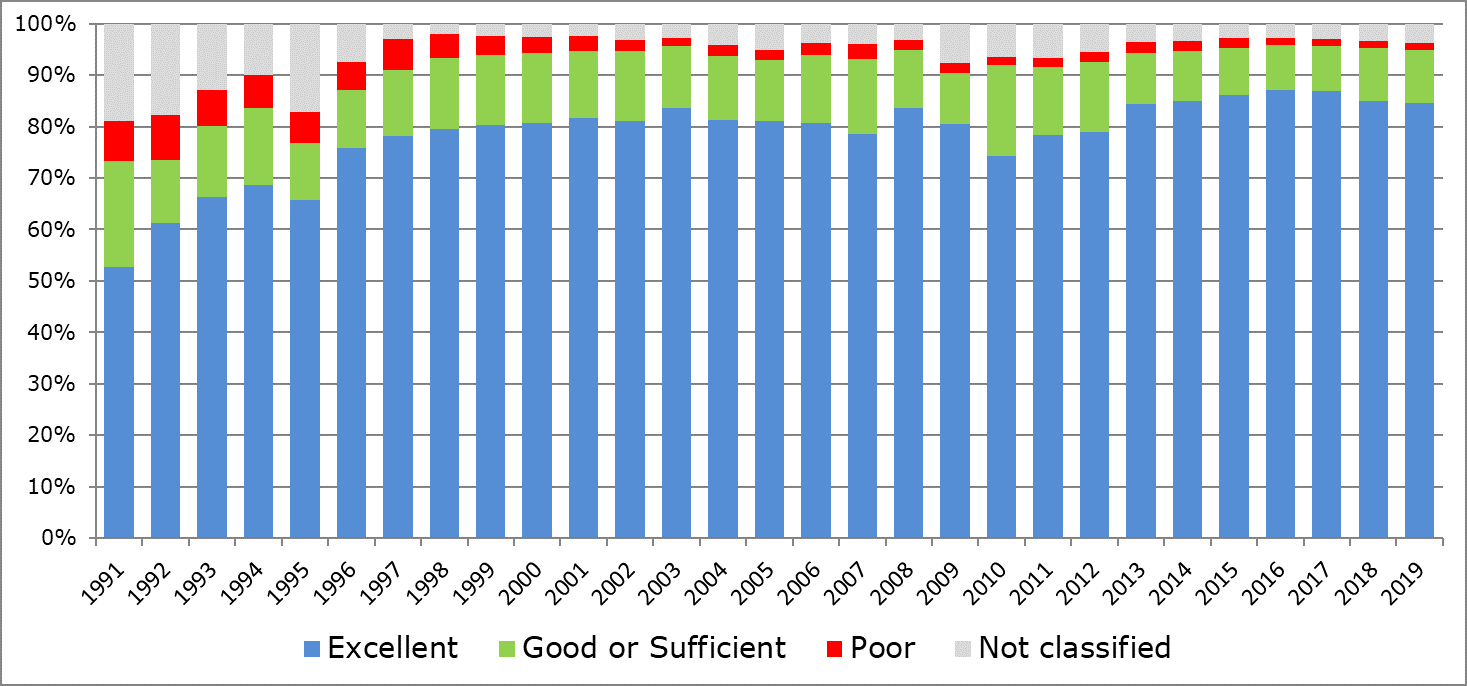

In recent decades, European countries[1] have not only begun to manage higher number of bathing waters, but have also significantly improved their water quality. Great efforts have been made at numerous bathing sites to reduce and eliminate pollution, and ensure safe bathing at thousands of bathing waters across Europe. As a result, the percentage of bathing waters achieving at least ‘sufficient’ quality (the minimum quality standards set by the BWD) increased from just 74% in 1991 to over 95% in 2003, and has remained quite stable since then. The percent of bathing waters at the highest water quality (classified as ‘excellent’) increased from 53% in 1991 to 85% in 2019. In other words, more than eight out of ten of Europe’s monitored bathing waters now have ‘excellent’ water quality (Figure 3).

[1] Beside EU Member States, data have been reported also by three non-EU countries: Albania (from 2013), Montenegro (2010-2011) and Switzerland (from 2009).

Significant investments in urban waste water treatment plants, improvements in sewage networks and other measures have contributed to a reduction in poor bathing water quality across Europe in recent decades. In 1991, 9% of bathing waters were classified as ‘poor’, whereas in 2019 this was the case for only 1.4% of bathing waters.

Figure 3: Bathing water quality in Europe since 1991

Source: WISE bathing water quality database (data from annual reports by EU Member States).

It is encouraging to see that more and more European bathing water sites have reached the minimum (‘sufficient’) water quality standard. It is even more reassuring to note that European countries are putting great efforts to ensure that more and more bathing waters are classified in the highest ‘excellent’ quality standard. Whilst most European countries began to improve the quality of bathing waters decades ago, Albania has undergone this process more recently, as explained in Box 3 below.

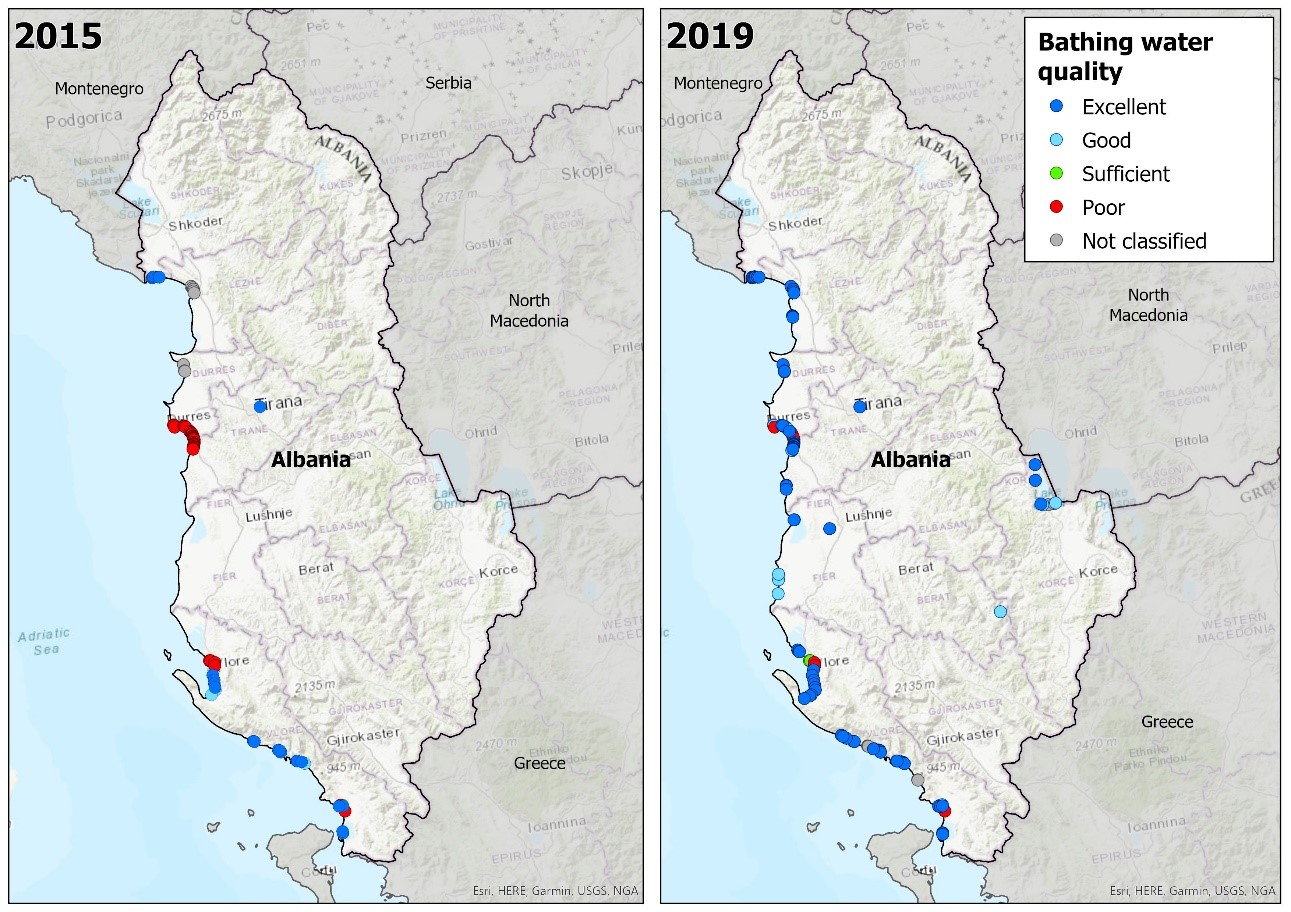

Box 3: Albania as coastal tourist destination

In 2015, almost 40% of bathing waters (31 bathing sites) in Albania were classified as ‘poor’. A great majority of these bathing water sites were situated on the coastline of Durres, one of the main tourist and country’s second largest city (EEA, 2016a). The national authorities have paid significant attention to the water sector in the Durres area in recent years. The World Bank also supported investments in the Durres water supply network, and the construction of water transmission pipeline to link villages to the city’s water supply system and reduce losses in the water distribution network. In addition, the local sewage network and its transfer capacity from the tourist beach area to the wastewater treatment plant were also enhanced (World Bank, 2014). In the recent years, five wastewater treatment plants providing treatment for almost half a million residents have been constructed in Albania (EEA, 2018).

These measures gradually contributed to better bathing and overall water quality in Albania. In 2019, only 7 bathing water sites (or 5.9%) were classified as ‘poor’ which is a significant reduction since 2015 when 31 bathing water sites (almost 40%) were assessed as ‘poor’. Improvement of bathing water quality offers great potential for coastal tourism. The tourism industry in Albania contributes more than 8% of the country’s GDP. Improving bathing water quality by ensuring clean and safe bathing waters is paving the way for Albania to become an established and well recognised tourist destination.

Map 1: Bathing water quality in Albania in 2015 (left) and 2019 (right).

Source: National boundaries: EEA; bathing water data and coordinates: reporting countries' authorities.

Clean bathing waters are not only essential for safe recreation, but also for the environment and economy. EU water policy has been successful in helping to protect and improve bathing waters in recent decades. What is the next step? One answer is revitalising bathing waters in cities, where the complexity of urban activities and pressures makes ensuring clean and safe bathing a significant challenge.

3.4. Now we can swim in some of our cities again

Since the Industrial Revolution began in the 18th century, the geographical distribution of human populations across Europe has changed significantly. In that time, Europe has become one of the most densely populated regions in the world, where almost 75% of the population lives in urban areas (Koceva, et al., 2016). The gradual increase in the proportion of people living in urban areas has come at a cost to European rivers and lakes over the last century. Many freshwaters were heavily degraded and polluted during this urbanisation process (EEA, 2016). As a result, traditional uses of rivers – such as bathing – disappeared. Large loads of wastewater flowing directly to the rivers and lakes made bathing impossible at such places without jeopardising human health.

In recent years, great progress has been made in improving water quality in European urban rivers and lakes. This is mainly due to construction of sewers and new waste water treatment plants, alongside upgrades to existing ones. Cumulative restoration measures – such as reopening covered rivers and improving water quality to bathing standards – contribute to how both local citizens and visitors experience urban rivers and lakes.

Restoring urban lakes and rivers which flow through big cities to the point where their water quality meets the bathing water standards is becoming more and more realistic and feasible. In recent years there has been a significant increase in the number of safe bathing waters situated in big cities[1]. In the last decade the number of urban bathing sites has increased substantially. About 75% of these bathing waters are coastal and thus situated in cities by the sea: with many on the Mediterranean Sea in cities of Nice (150 bathing waters), Pesaro (almost 90 bathing waters) and Toulon (70 bathing waters). The cities with the highest number of inland urban bathing waters are Amsterdam (38), Stockholm (36), Berlin (33), Lugano (28), Geneva (25), Rotterdam (23) and Vienna (23).

Today, safe bathing is possible even in some European capitals; people can bath on the banks of the River Danube in Vienna and Budapest, on the River Spree in Berlin, numerous places in Amsterdam, on the River Daugava in Riga, at Copenhagen Harbour (Box 4) and many others.

Whilst bathing water quality in the Europe is increasing, and bathing is today possible even in some heavily urbanised areas, there is the still a need for integrated and adaptive management to mitigate both existing and emerging pressures, as outlined in the following chapter.

[1] Urban areas reported under UWWTD as »Big cities« and urban areas (agglomerations) as identified by JRC in riparian zones spatial data.

Box 5: Management of large bathing waters in Barcelona (Spain)

Barcelona has a population of 1.6 million inhabitants, with 1.5 million more in the wider metropolitan area. The seafront of the city has been transformed, and it is today a key tourist site, with over 10 km of beaches, visited by over three million tourists each year. Due to its high population density and hilly terrain, Barcelona’s bathing waters are exposed to sewer systems overflows. These overflows cause episodes of short-term water contamination which may affect the quality of bathing waters. As is common in Mediterranean climates, heavy rain events are often concentrated in very few days with high intensities.

Up to the early 1990s, Barcelona faced flooding problems and overflows, causing environmental pollution. In 2006, an ambitious plan was proposed, with improved environmental and public wellbeing objectives: to reduce the combined sewage outflows so that the number of hours that the bathing waters are not allowed for bathing is reduced.

Information systems have been developed for both internal coordination and general public information. The public can access bathing information (bathing water quality predictions, weather forecast, presence of jellyfish etc.) using electronic panels at the beach and on public web pages. A coordination protocol is activated by the detention of an overflow, which can be triggered by tele-controlled sensors, camera images or direct observations at the beach. The protocol describes different responsibilities so that the responsible agent can diagnose the outflow and take correction measures for the immediate resolution of the problem

In the paragraph “The initial Bathing Water Directive reflected the state of…” it should be mentioned that the new Bathing Water Directive focusses only on measurements of bacteria since the WFD is already measuring nutrients and chemicals in order to improve the water quality. Therefore, this does not need to be monitored by the new BWD anymore.